Most people of a certain age can probably recall their discovery of the first local newspaper carrying their favorite comics. It almost doesn’t matter what those comics were, as there was something for everyone. I never read Prince Valiant. Too cheesy. I did read Blondie but felt it hit a little too close to home. Beetle Bailey. Fun. Peanuts? My ‘peeps’. Li’l Abner? Could have been one or two of my neighbors. Hi and Lois? Too vanilla. I’d follow some or all of these in glorious black and white during the week, and on Sunday, magically, we found that they had all erupted into living color. We were too young to understand that the comics had two reasons for existing. First they were entertaining. Second, they trained children (future subscribers) to get into the habit of reading the daily newspaper.

Growing up in Milwaukee we had two choices. There was the morning Milwaukee Sentinel and the evening Milwaukee Journal. I was one of those “paper boys” who got up early in the morning, picked up my bundles of Sentinels and delivered them to homes along my streets on the south side of Milwaukee. I earned more money than my days of setting pins at the local bowling alley, but after a year or so decided the little bit of income it provided wasn’t worth the effort. Besides, I was part of a 4-piece band which gave me more spending money than the paper so, hey, why not stay with rock ’n roll.

The Milwaukee Sentinel had long been a money-loser for William Randolph Hearst’s empire. Matthew J. Prigge wrote in the March 2016 Shepherd Express “Hearst hung on to the Sentinel, losing money every year, until his death in 1951. Hearst Publishing continued ownership until a strike in 1962 shut the paper down for six weeks. With Hearst Publishing prepared to fold the paper altogether, the Journal Company stepped in at the last moment and—feeling that Milwaukee needed more than one voice in its daily news—offered $3 million for the sheet.” For the next 30 years the papers continued to be published as separate entities, only to be merged into a single paper—the Journal-Sentinel—in 1994. Milwaukee wasn’t the only city to become a one-newspaper town. As the century turned, cities all over the country saw their two-newspaper towns become one newspaper towns, and many smaller cities and towns watched as their local papers shrunk, merged, or closed down altogether. Print media was becoming increasingly concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer publishers.

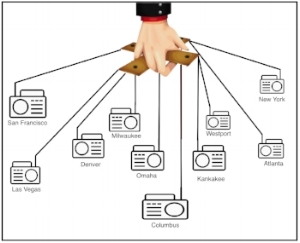

Radio and television suffered a different fate. The Federal Communications Commission has long been the radio and TV regulatory arm of the federal government. For most of the post-war period (beginning in 1953), companies were allowed to own no more than one AM, one FM, and one TV station in any one media market. Furthermore, they were limited to a maximum of seven of each nationwide. Period. The original 7-station limit was to prevent any one company from having undue influence over the American public by dominating the media, locally, regionally, or nationally. During the 1980s this restriction was seen as “heavy handed”. Under the Reagan administration the FCC saw fit to allow companies to own as many as 12 AM, 12 FM, and 12 TV stations. Got the math: companies could now control 36 broadcast outlets nationally. With a straight face and a nod to George Orwell, in 1984 the government told us that fewer companies owning more stations would “encourage media competition”. The FCC concluded that the concentration of media in fewer hands posed “no threat to the diversity of independent viewpoints in the information and entertainment markets.” The new rule included another trigger. In 1990 the FCC would further relax the broadcast ownership by any one company to, well, unlimited. A little more than a decade later alarm bells began going off. According to Deadline Hollywood, by spring 2007, “91% of the total weekday talk radio programming was conservative, and only 9% was progressive. . . .” And those numbers are more than a decade old.

Obviously media consolidation has done nothing for diversity. iHeart Media now owns 845 stations in the United States. Cumulus Media owns 500 stations. Other companies like Entercom, Cox, Clear Channel, and CBS, are approaching another 1000 stations in total. Both iHeart and Cumulus are operating in bankruptcy, and bankruptcy means there will be little interest in balanced programming or local concerns, and more interest in cutting costs. As management focuses on "efficiencies", many of these corporate-owned radio stations will have little or no staff in the cities and towns they serve, enabling them to save money by doing away with local hosts, local news, and local weather. The “local” newscast you hear in Topeka might be coming from a voice in Chicago. And that’s on top of corporate ownership that caters to the expansion of a conservative audience mind-set. Then there’s Sinclair, the conservative broadcast business which is expanding (perhaps soon to own 200 television stations) and vying with Fox to become a kingmaker in American politics by shaping and supporting conservative opinions in the vast majority of American media markets.

This is not meant to be a sentimental look at 'the good old days', or an exercise in hammering large corporations. It is rather a recognition that as technology continues to evolve we need to hold precious those things that we've come to appreciate including the importance of local radio stations, newspapers and magazines, with local information, prepared by local people. The adage to "Think Globally, Act Locally" has never been more appropriate.